In October 2024, Senior Management of the European Central Bank (ECB) Market Infrastructure and Payments division published a hit piece on Bitcoin. The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis followed suit shortly thereafter. The ECB paper provides an overdue perspective on Bitcoin from central bankers. We should take it seriously for two reasons:

First, because its assessment of Bitcoin usage is fundamentally wrong. (It should be noted that the same authors predicted Bitcoin’s death in 2022).

Second, the authors still manage to contend that “promoters of this investment vision put little effort relating Bitcoin to an economic function which would justify its valuation,” despite the myriad papers, books, and analyses of Bitcoin (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.).

Given the source and timing of this paper, supporters and detractors of Bitcoin alike should now recognize how serious this debate is. The ECB is an authoritative institution in the world of central banking. Is the ECB dismissing Bitcoin’s value proposition mere hubris or the start of a coordinated crackdown on Bitcoin from global institutions? (Matthew Kratter suggested the ECB is paving the way for its digital Euro.) The ECB’s paper may be a signal of what is coming in the policy pipeline.

I will unpack the main arguments put forward in the paper, reveal their shortcomings and unstated assumptions, allowing readers to keep a balanced perspective in mind. The paper has many issues, but I will focus on the central tenet, the (negative) distributional consequences of Bitcoin.

Argument 1: Bitcoin exacerbates wealth inequality

The authors argue that as the price of Bitcoin appreciates, economic value is redistributed throughout society. “The wealth effects on consumption of early Bitcoin holders can only come at the expense of consumption of the rest of society (…) If the price of Bitcoin rises for good, the existence of Bitcoin impoverishes both non-holders and latecomers.”

The authors make this assumption based on the theory of “rational bubbles (…) where asset prices deviate from their fundamental values but persist due to the collective belief that prices will continue to rise.” The theory (Tirole,1985) posits that “overpriced assets (relative to their fundamentals) emerge in environments where no alternative, fundamentally-driven asset has a better yield than the bubble asset.” The authors also cite Blanchard and Watson’s (1982) description of how “bubbles can persist under rational expectations as long as agents believe that they can sell the asset to someone else at a higher price in the future.” Essentially, a “greater fool theory” at work.

Response to Argument 1

Let’s address the relationship between early adopters and non-Bitcoin holders first. The “greater fool theory” presented by the ECB makes Bitcoin the most elaborate scam in the world.1 For the sake of simplicity, if we set aside cases where Bitcoin is used as a direct medium of exchange, it is true that the only way to profit off of Bitcoin relative to fiat is to sell at a higher value in fiat from when it was first purchased and to spend that value relatively quickly. High Bitcoin returns relative to fiat require an ever-growing number of people buying into Bitcoin, but since there is a finite number of people, price appreciation will slow, halt, and then crash.

But there are major problems with this greater fool theory.

As the saying goes, “Fiat has no bottom.” Money issued with the ‘full faith and backing of its government’ is inflationary more often than not, a melting ice cube that is constantly getting devalued. Central banks always succumb to the temptation of increasing the heat and adding more ice. Asking whether global demand for Bitcoin will turn negative is like asking whether we expect hyperinflation cycles to go away anytime soon. The answer is no, because there will always be a demand for a store of value that isn’t tied to a specific geography. For that reason, it is much more logical to expect non-Bitcoin holders to appear poorer than Bitcoin holders over time, everything else being equal. Goods and services don’t get more expensive over time, they are the same relative to each other, but it’s the fiat unit of account that goes down relative to those same goods and services. That’s why prices go up, and it’s why some of Bitcoin’s price goes up. Non-Bitcoin holders are poorer over the long run because their wealth was expropriated by the state, not because of a transfer of value from fiat to Bitcoin.

Bitcoin has a market cap of $1.3 trillion. As a currency, it can’t possibly be competing with the dollar, when total assets directly denominated in U.S. dollars are more than $100 trillion. But it is competing with gold (market cap currently at $18.7 trillion).

Since the authors are so eager to pull on the heartstrings of “wealth inequality” in their arguments, Bitcoin also solves the fundamentally unfair and inequitable Cantillon effects (the closer you are to the source of money creation, the higher your share of the wealth created), which rob the middle and lower classes on a fixed income of their hard work.

What about the distributional claim? Are latecomers impoverished relative to early adopters? To answer that question, we first need to address a more pernicious claim the authors snuck in, which is…

Argument 2: Bitcoin price increases are not driven by increases in the productive potential of the economy

The ECB argues that because Bitcoin is only used as an investment vehicle and not a medium of exchange, wealth increases from saving in Bitcoin happen without any commensurate increase in productive capital and efficient allocation. It is framed as a zero-sum game. Any wealth generated from Bitcoin’s price appreciation does not come from new value creation but only from a shift in existing wealth. In other words, when your Bitcoin appreciates, you are stealing value from someone else who bought into Bitcoin at a later date (or didn’t buy it at all).

Let’s Unpack Argument 2

The authors start with basic production theory whereby new technology can increase the overall economic production potential which ultimately translates into an inflation-free expansion of the consumption potential. Think of the benefits to society of freely available Large Language Models (LLM). Technological improvements like LLMs increase the total factor productivity which in turn leads to a more efficient allocation of factors of production. A collectively desirable “wealth effect” is generated as a result, like a tide that lifts all boats.

But in some cases, productivity increases do not cause a corresponding wealth effect. For example, the authors contend that innovations in public administration only trickle down to the rest of the economy indirectly. But that is not what the authors are arguing. The rational bubble argument says that “soaring stock markets can increase the marginal propensity to consume through wealth effects even before the actual increases in productivity have materialized in anticipation of future real wealth increases. However, the market valuations (…) can obviously be based on a misjudgement by investors.”

Let’s talk about those “misjudgements.” Securities and Exchange Commission filings earlier this year have shown more than $11 billion of institutional investors now buying into the Exchange Traded Fund. Why is that?

In the current inflationary monetary system, economic actors are incentivized to overconsume. Why hold on to a melting ice cube? Economic actors are also incentivized to be over-indebted. Why not borrow now since the debt will be worth less over time? But with Bitcoin, large companies can now save value on the internet with no counterparty risk. This was never before possible.

Large private firms, ETFs, and small countries are now mostly dictating the price level of crypto. The Saudi sovereign wealth fund can’t store $800 million in Bitcoin without expecting to lose 2% of its value if they withdraw $400 million, but that could change one day. It’s much too late to be making claims that investors are all “misjudging” the market. We’ve had many boom and bust cycles since 2010, and the authors even predicted Bitcoin’s death in 2022; to say that “everybody is just misjudging the market” seems implausible at this point.

Bitcoin is a hard asset that is increasingly liquid and highly salable. It makes firms and individuals future-oriented savers, and as a result enables both capital accumulation and a more efficient allocation of resources. The collective benefits to society are in fact incalculably large. Not only would the ‘freed up’ capital from inflationary forces generate massive increases in the total factor productivity, but the fewer economic distortions will allow a much more efficient allocation of capital.2

Gone are the “zombie” companies surviving on cheap credit paid for by the taxpayer. Instead, more companies are rewarded for making the right allocations of capital to support innovative endeavors. Since the savings asset cannot be manipulated by central planners, we end up in a more stable long run environment.

Capital is also freed in the remittance market. Sender banks generally charge between $5 and $25, and each intermediary bank involved may add correspondent fees, which can drive total costs up to $30 or more per transaction. Additionally, the recipient’s bank may charge fees to accept the funds, and SWIFT transfers usually take 1-4 business days to settle. With Bitcoin however, value is exchanged peer to peer with no intermediary taking a cut. Each Bitcoin transaction (UTXO) takes up a certain amount of bytes on-chain. In order to move a UTXO one submits their transaction to a pool along with a fee. The ratio of the fee to the UTXO size gives you the fee rate of Satoshis per Bytes. Fee rates are a free market. People bid to get their transaction into blocks. If the fee matches or exceeds most other transactions one can prioritize their transaction into one of the next few blocks. The fee rate varies at the extremes from 5 sats/vB up to 2,000 sats/vB. For the last year it’s been between 10-100 sats/vB most of the time. $817 billion were sent in remittances globally in 2023 alone. The size of transfers varies a lot but let’s average it to 2 million transactions a day. How much productive potential capital are we freeing by using Bitcoin instead? Let’s conservatively assume Bitcoin costs 1$ per slow 24-hour transaction and that the average cost of an international SWIFT transfer is $30 for the sake of simplicity. (Globally, sending remittances costs an average of 6.35% of the amount sent.) That’s easily $21 billion dollars saved annually from transaction costs alone.3

As noted before, even the ECB authors reluctantly admit that the shift from fiat to Bitcoin generates a “wealth effect” when the price of Bitcoin rises relative to fiat. That wealth effect will be more pronounced for first-mover corporations with large amounts of cash like Microstrategy than for latecomers like Apple or Microsoft. But crucially, even latecomers will be better off at the limit (i.e., if Bitcoin becomes the dominant currency) compared to holding on to large amounts of ever-debased government paper.

So are latecomers penalized relative to early adopters? No, because there are massive productivity gains at both the individual and collective levels. In a world where a large part of the world’s assets are stored in a deflationary digital asset, saying a latecomer is penalized by an early adopter is like arguing that the productive output I generate from working today is stolen from people born after me. It makes no sense. Innovation creates new economic value and makes the economic pie larger. We are not merely swapping ownership of Bitcoin, we are making gains from trade, freeing capital for investment and making real prices drop relative to Bitcoin. That is what’s supposed to happen as the real economy grows and we get more productive. Sixteen years after its creation, Bitcoin will soon operate on a multigenerational time scale. There will always be more people coming of age contributing to society, and many of them will use Bitcoin. It is a paradigm shift, a giant leap forward in monetary technology, that some people still can’t (or don’t want) to wrap their heads around.

Argument 3: Bitcoin wealth is more concentrated than other wealth

The authors also declare that “Bitcoin related wealth is more concentrated than other wealth.” The evidence for this assumption? “Research found that the Bitcoin ecosystem is dominated by large players, be it miners, Bitcoin holders or exchanges… [I]individual investors collectively control 8.5 million Bitcoins, i.e. less than half the Bitcoins in circulation by the end of 2020, and within individual holdings, there is significant skewness in ownership; the rest of the Bitcoin is held by large miners or exchanges (Makarov and Schoar 2021).”

It is possible the authors didn’t realize that exchanges like Coinbase (which currently holds around a million Bitcoin), only hold them in custody as liabilities for other entities like Blackrock and Fidelity. Coinbase manages a million-odd Bitcoin on behalf of other parties. The Company only owns around BTC 10,000.

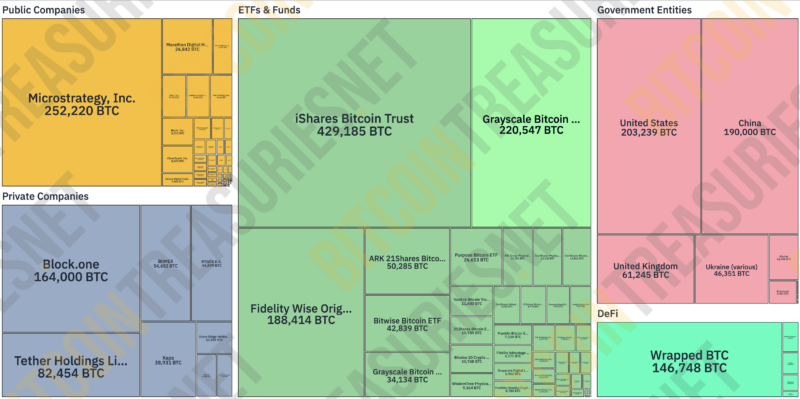

As we can see from the ownership distribution chart below, as of November 2024, the ecosystem is not, in fact, concentrated in the hands of large players. Let’s assume that the current operating supply is 16,000,000 which includes 1.57 million that are yet to be mined.4

The maximum supply of Bitcoin will only ever be BTC 21 million. The entity known as Satoshi Nakamoto holds a private key with an estimated 1.1 million BTC that has remained untouched since December 2010. It is likely lost or given away as a network subsidy to bootstrap the network. Further, around 4 million BTC are estimated to be lost forever by their holders.[/efn_note] Table 1 shows about 72% of the coins in the hands of private persons. Are Dollars, Renminbi or Euros also dominated by a few large players? If we realize that the richest 1% of the world’s population hold 50% of global wealth, is that a result of the underlying monetary technology?

Source: Bitcointreasuries.net

Table 1. Distribution of Bitcoin ownership

Source: Bitcointreasuries (except for miners)

What the authors ignore: geoeconomic shifts in currency power

The authors ignored the geoeconomic paradigm shift currently underway. The USG has weaponized world payment rails by its dominance of correspondent banks and the SWIFT networks and the reliance of the world on the dollar. The extent to which U.S. weaponization of payment rails will negatively affect the propensity to hold dollar denominated assets remains an open question. BRICS countries, who have a collective interest in challenging dollar hegemony, face serious coordination problems and conflicting interests. What is certain however, is that changes to how money flows will carry significant short to medium term market uncertainty. Here is a quick geoeconomic recap of the last few months:

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) abandoned its participation in project mBridge, allowing China to lead the way

Central banks have significantly increased their gold reserves

BRICS are openly discussing new means of engaging in bilateral trade (cite)

BRICS members (the UAE, Argentina, Ethiopia) are mining Bitcoin using public resources

The US Treasury secretary is concerned with Tether and wants to develop a public-sector CBDC replacement.

These trends will likely accelerate Bitcoin’s use as a medium of exchange for large trade transactions. Yet the ECB authors are quick to dismiss that possibility. So even if the price appreciation was based on serious misjudgement by investors, when two central bankers with a very strong interest in preserving their paradigm call it a “speculative bubble,” there are grounds for skepticism.

The timing of these papers confirms what everyone in the Bitcoin world already knew. Central planners think that: 1) fiat vs. bitcoin is a zero-sum long game, 2) demand side dynamics will always be ignored out of hubris or self-preservation 3) central bankers are freaking out at the prospect of losing control.

The post Digital Assets Series: Part 4 | The European Central Bank’s Attack on Bitcoin appeared first on Internet Governance Project.

Source: Internet Governance Forum